I was very tempted to choose A Doll’s House as the play for my Written Assignment as there really are many interesting themes and bits of analysis, though I ended up being swayed by Patrick Suskind’s Perfume. I’ve included a practice essay I wrote on the play, as well as some notes on:

- Context

- Character analysis (Nora, Torvald, Christine and Rank)

- Symbolism

- Scene analysis

The essay I wrote was based off the question: By what means and to what effects does Ibsen use the convention of a significant arrival and/or departure to enrich their work?

Cultural Context and Background

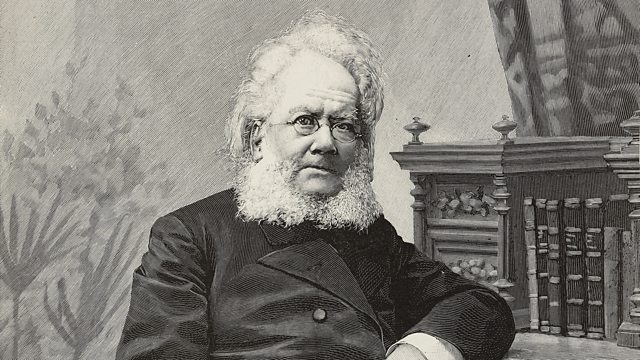

Henrik Ibsen

- Born 1828 in Norway into upper-middle class

- Originally wealthy family but then father became bankrupt when he was 7 years old

- 1862 self-exiled to Italy

- Moved to Germany in 1868 and wrote A Doll’s House

- Married in 1858 and had one son –. Believed that husband and wife should be equal. Critics attacked him for disrespecting the institution of marriage in the conservative environment

Inspiration for A Doll’s House

- Based of Laura Kieler, a woman in his social circle

- He sought to create a sense of realism and nationalism in his works

- Could have been inspired by the wave of revolutions across Europe in 1848 — large tide of liberalism in the Spring of Nations

Political situation in Europe

- Strong nationalism rising in countries

- Greater interconnectivity – formation of alliances and diplomatic interactions

- Age of industrialisation and social activity (uprisings, revolution)

- More active populations

- Economic boom brought about more awareness about money

- Sexist – women still seen as homemakers in society

- Society dominated by aristocracy of professional mean (lawyers, bankers

Realistic Theatre & The Well-made Play

- Realism strives to portray life accurately and shuns idealised visions of it.

- In A Doll’s House, Ibsen employs the themes and structures of classical tragedy while writing in prose about everyday, unexceptional people.

- A Doll’s House also manifests Ibsen’s concern for women’s rights, and for human rights in general.

Well-made play:

- constructed according to certain strict technical principles that dominated the stages of Europe and the United States for most of the 19th century and continued to exert influence into the 20th.

- Incidents follow in chain of cause and effect

The technical formula of the well-made play, developed around 1825 calls for

- complex and highly artificial plotting

- a build-up of suspense

- climactic scene in which all problems are resolved

- a happy ending.

- A Doll’s House deviates quite a bit from the conventional well-made play — “happy ending” is quite subjective.

- Contains careful exposition that lays the groundwork for the ending — see Nora’s character growing and breaking out of the mould of a conventional housewife

What is the context of a Dolls’ House? How does the play reveal its context?

A Doll’s House is a play written by Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen in 1879, during his residence in Germany. It is centred around the Helmer household in 19th century Norway which reflects the conservative society, particularly in relation to gender norms. Nora Helmer very much embodies the conventional housewife whose life revolves around her husband and children, and society is dominated by aristocracy of professional men like lawyers and bankers such as her husband Torvald Helmer. However the play reflects the rising liberalism across Europe encouraged both by the age of industrialisation and 1848 revolutions of the Spring of Nations; as well as Ibsen’s own progressive views on women’s rights and equality between sexes in the institution of marriage.

The structure of the play follows the classical structure of a “well-made play” while writing about everyday, unexceptional circumstances It shuns the idealised versions of life, instead portraying characters and events that would have been considered quite controversial and shocking to an 1800s audience. The play follows the careful exposition with appropriate suspense and careful exposition that lays the groundwork for the ending — the audience follows Nora’s character on a journey of growing and breaking out of the mould of female subservience.

Nora Helmer

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/norahelmer-58c9e0393df78c3c4fb73fc4.jpg)

Conflict experienced by Nora

- Leaving a husband who, by societal standards, has not done anything wrong nor abusive. Learning to develop her own opinions and judgement

- Leaving her children

- Trapped by her biology – women being obligated to children

- She does not have the mental fortitude to blend the personas of mother, wife, and human being

| Torn | Torn between her desire to lead a life that she wants and her obligations to her family. Also torn about her dissatisfaction with a husband who, by societal standards, has not done anything wrong. |

| Clever | Knows the power of her looks and beauty to manipulate and gain her husband’s trust. Nora talks incessantly about being beautiful and knows how to manipulate Torvald.

|

| Trapped | Boxed into the gender norms of a 19th century housewife with no decision making power nor financial mobility. |

| Dynamic | Gradually develops and learns to trust her own own opinions and decision making calculus. |

| Fragile | Nearly crumbles under the pressure of her choices. Does not have the mental fortitude to withstand Krogstad’s blackmail and sinks into a frenzy, contemplating suicide.

She behaves like a helpless, naive woman and constantly asks for help, and almost greedily accepts Torvald’s patronising endearments “skylark”, “squirrel”, “little creature”, “silly girl”. Ibsen reinforces the notion that she is like a pretty, frivolous plaything, a vulnerable person in need of protection. |

| Wife | The doll of her husband – dances for him, manages the home for him, dedicates herself to his welfare. |

Character motivations

- Shifts throughout the play

- Protect her husband’s reputation and save her husband’s life

“Nobody would’ve believed me but I would’ve denied it”

“Thousands of women have [sacrificed their honour]” to protect their husbands

- Protect all the men around her

- Protect dying father by forging signature

- Product of her society — raised with no other option of being the doll that she was

- By the end of the play, Nora desires to live her life by her own standards

Ibsen’s intentions through Nora’s character

- Changing gender roles

Nora’s character revolves around her role both as a woman in 19th century Norway society, with her most deep-seated fears and driving motivations rooted in these two identities. At the start of the play, her motivations are mainly to protect all the men around her. As a wife, she saves her husband’s life not only physically through borrowing money to pay for a recuperation trip to Italy, but also his reputation and honour which he prizes above anything else by aiding his recovery and obtaining the loan through underhanded means. As a daughter, she protects her dying father from the struggles her family is going through by forging his signature. However, there is a shift in Nora’s motivations throughout the play where she gradually starts to push her own desires to the frontline and prioritise living her life to a standard she believes she is deserving of.

The dynamic nature of Nora’s character reveals Ibsen’s intentions of illustrating the changing role of women in Norwegian society. By the late 1800s as Norway underwent industrialisation women saw an elevation in terms of education and their roles in households, as well as societal roles. Nora embodies a stereotypical housewife liberated in the progressive lens of Ibsen’s views towards women’s rights, prioritising her identity as a human being above societal obligations of a mother, wife and daughter. He also illustrates the difficulty of the individual embroiled in the changing gender roles, with Nora having to confront the fact that she is at odds with the rest of her society, despite being a product of it and conforming for the whole of her life to being a doll of the menfolk. She has to actively sacrifice her family, leaving her children, and this dramatic ending is both empowering and saddening. Ibsen could be attempting to enlighten audiences through Nora’s role about the difficulties women in their society face, encouraging more support for women boxed within these marginalised, conservative norms.

- Humanistic mindset

Ibsen also wanted to focus on the idea of authenticity of the self. Society is too narrow and confines individuals to fixed moulds. Tries to unveil society and show people the truth is what it is. Torvald is as stereotyped and confined as Nora is. Exhibits how confining the ideas about morality are, how rigid societal structure is that shoves everyone into a dollhouse, a symbol for society and the state. We are all dolls living within this structured house, puppets of societal norms. Helmer household is a microcosm for society. There is more than a one-dimensional identity of a woman, or a man, or morality, and humans exist on a spectrum. Much broader message than just women — the men are very much products and victims of society. Nora eating macarons shows how hard it is to confine her personality on little things, the individualism and spirit of rebellion is present from the very start of the play. She was never completely passive or submissive, just that her desire to fulfil societal obligations weighed out.

Torvald Helmer

| Traits | Evidence |

| Overbearing | “You have no idea what a true man’s heart is like […] there is something so indescribably sweet and satisfying, to a man, in the knowledge that he has forgiven his wife” → he is empowered

“Empty. She is gone” → realisation at the end of the day that Nora is no longer his. “[a hope flashes across his mind]” — possible hope of revelation. Epiphany at the end of the play. |

| Patronising/tender/gentle | Kind to his wife. Treats Nora more like a child than his wife. In Act 3 he even says Nora is “doubly his own” because she has “become both wife and child”.

Calls her silly names, scolds her for eating macaroons Not just a child, a doll — she dresses up and dances to please him. |

| Rigid views | Very conventional, set-in-stone beliefs about morality.

Torvald is a character that is as much a product of his environment as Nora is. Ibsen created in Torvald nothing more than what he considered a typical Victorian male. In a way, he is equally as imprisoned as Nora is. Neurotic horror of debt — debt anxiety rife in the 1800s due to bourgeois values |

| Hard worker | Nearly killed himself over his job. Takes immense pride in his work, prioritises his career and the reputation it brings above all. |

| Lack of self-awareness | Tragic flaw!!

Does not understand himself. Relishes being the all-knowing provider, sees himself as a heroic figure. Does not realise that his wife is not reliant on him.

|

Discuss Torvald’s journey and possible redemption. What does his character reveal about Ibsen’s intentions?

Torvald’s character is one that incites an instinctive backlash from modern-day readers, especially women of the 20th century, at his overbearing and patronising hyper-masculinity. This is reflected in the way that he treats his wife Nora more as a plaything and a child than as a partner on equal footing, calling her demeaning endearments such as “frightened little singing-bird”, “skylark”, “little creature” and “silly girl”. He believes himself to be her protector, the one who shelters her from harm. Yet Torvald lacks the self-awareness to not only see that Nora is much more independent and is the one making the decisions to protect him; but also that he is not the noble, benevolent husband that he believes himself to be and contrary to his promises of risking his “life’s blood, and everything” for Nora, when push comes to shove he chose to prioritise his own selfish desires over his wife. This serves to be his tragic flaw, pushing Nora’s rose-tinted lens that she sees him through to shatter and for her to leave him. But even as modern audiences may recoil from his demeanour, Ibsen’s play is one grounded in realism where Torvald reflects the typical Victorian male. He is as much as a product of his society as Nora is and the rigid views on gender roles and morality have been inculcated in him from birth. Ibsen could be attempting to illustrate how deeply-rooted our beliefs and opinions are in our environment, and that gender roles are not only a one-sided harm to women only.

However, there is hope in the end of the play for a possible redemption, where just before the door slams and Nora leaves, Torvald seems to have an epiphany of sorts.

Christine Linde

| Pragmatic, Independent, Self-sufficient | “I have learned to act prudently. Life, and hard, bitter necessity have taught me that”

→ To support her sick mother and younger brothers she sacrificed her love for Krogstad. Selfless, pragmatic. |

| Represents ideal woman | “We two need each other”

Her relationship with Krogstad in Act 3 seems like a mutually-dependent and healthy one. Breaks the mould of a stereotypical Victorian woman – actively seeking work and taking pride in it. |

| Relationship with Nora | Christine represents Nora’s past. Christine remembers Nora as a child, as the girl who lived in her father’s home.

Christine is the force that pushes Nora’s character development |

Ibsen’s intention with the character of Christine:

Christine could represent a critique of Ibsen towards society. Because once Christine is freed from societal responsibilities, she cannot live outside the role as a caretaker. She is unhappy and longs to be “a mother to someone”, namely Krogstad’s children, unable to seek fulfilment. As a liberated woman, she gladly assumes back her role as a wife and mother in Krogstad’s household, because she is unable to find a sense of purpose elsewhere. This reflects Ibsen’s commentary that women have essentially been indoctrinated by society till the only role they understand is one of a homemaker.

“Nils, give me someone and something to work for”

“It is nothing but a woman’s overstrained sense of generosity” – Krogstad

“A home to bring comfort into”

The major difference between Christine’s new relationship and that of the Helmers’ seems to be that Christine and Krogstad are entering into it as equals. Christine says to Krogstad:

“Nils, how would it be if we two shipwrecked people could join forces? […] Two on the same piece of wreckage would stand a better chance than each on their own.” (3.42-3.44)

Perhaps, the union of Nils and Christine is Ibsen’s example of “the most wonderful thing of all,” which Nora defines as “a real wedlock” (3.376-3.378).

Dr Rank

Provides exposition on Krogstad

- Tells Christine and Nora that Krogstad “suffers from a diseased moral character”

- Explains his history as a criminal

Reveals Torvald’s superficiality

- Rank decides not to tell Torvald about his impending death

- “Helmer’s refined nature gives him an unconquerable disgust at everything that is ugly; I won’t have him in my sick-room”

- Torvald has a childish aversion to anything remotely unattractive. Sheltered and protected by his loved ones.

- Doctor Ranks is extremely aware of both himself and those around him.

Reveals the flaws in Helmer’s marriage

- He is the subject of Nora’s fantasies, of having a rich man leave behind a fortune to take care of her

- Exposes the distance between the Helmer couple. Nora confides in Rank that “being with Torvald is a little like being with papa.”

- Nora treats Rank as a confidante, admitting that she feels trapped in her marriage

Symbolic – speaks of moral disease and his own illness

- Tuberculosis of spine — could represent the diseased backbone of society (unenlightened)

- His own death coincides with the death of the Helmer’s marriage – card with black crosses come in same box as Krogstad’s letter that shatters Helmer’s marriage

Symbolism

Festive setting

Christmastime / New Year’s Day

- On the cusp of a new year

- Start of play – Torvald looking forward to new job (extra money and prestige) and Nora anticipates paying Krogstad back

- By the end of play — symbol has shifted

- New Year represents new start being embarked on by both Nora and Torvald who both face radically changed lifestyles

- Nora leaves in the harsh, unforgiving landscape of winter. Makes her resolve to leave the marriage and forge out alone even more impressive.

Christmas tree

- Decorative purpose — Nora fusses over the tree. Mirrors her own value in household as a pretty doll to entertain and charm Torvald.

- Kept secret from Torvald — reflects Nora’s secretive nature and independent streak when she tells maid to conceal it from Torvald from the beginning of the play. The Christmas tree represents Nora’s domain.

- Symbolic of the Helmers’ disintegrating marriage. Pretty ornaments and facade fall away to reveal the ugly, bare truth

- Mimics Nora’s psychological state

- Act 2 stage directions “Christmas tree … stripped of its ornaments … disheveled branches”. Deterioration of tree right after Nora receives blackmail from Krogstad

- Withers as play goes on — could parallel Nora’s growing dissatisfaction at her life. Tree is a symbol of Nora’s duties in the household.

Tarantella Dance:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-541769104-37acac8f56fb4c48b2b61544433bae98.jpg)

- Her lifeline, keeps her alive

- “Dancing as if your life depended on it” (Torvald)

- “You have forgotten everything I taught you” — Could it symbolise her truly breaking free of patriarchy?

- When Nora dances the Tarantella, the audience sees her as both infected and trying to ward off the poison. Represents the poisin of society: the rules and expectations that inhibit her.

- Symbolises Nora’s last attempt at being her husband’s doll — dances in a very violent and sexual manner, in a way that could suggest trying to salvage their relationship. She dances to maintain her appearance with him before her life and their relationship is shattered by the letter

- Frenzied spinning dance traditionally played at weddings

Stockings and Macaroons

Symbolism in the play is derived from techniques of naturalism — explores the relationship between people’s behaviour to their environment. Symbols are apparent trivialities in life: macaroons and silk stockings.

Stockings represent immorality – scandalous of a woman to show a man unrelated by blood or marriage in that era

Stockings represent immorality – scandalous of a woman to show a man unrelated by blood or marriage in that era- Connected to sexuality and manipulation

- Nora is fully aware of her own beauty and uses her sexuality to manipulate men like Dr Rank

- Macaroons and frivolous, luxurious, sugary and unnecessary. Contradictory to Nora’s claims of debt and money-troubles. Suggests that she is indulgent and forwards the image of her being frivolous.

- Exposes Nora’s fierce independent streak — goes to buy sugary food when she has no money and lies to her husband. Her own way of keeping a semblance of control.

- Not just symbol of deceit, but part of the flirtation game between Torvald and Nora→ Torvald finds it endearing that Nora eats sugar. He gets pleasure and is physically attracted to a woman who is his possession. His dictation over Nora’s habits makes him feel that he has power over her

Dress (Capri)

- Nora wants to tear up herdress

- “I should like to tear it into a hundred thousand pieces”

- Represents the confinements — even when she is in terror and at a loss she is expected to put up a pretty facade and be beautiful

- Symbol of when Nora went to Italy and had best time of her life → now represents debt

- Nora has to stitch it up and dance in it

- Represents her marriage and masquerade, hiding the truth from Torvald

Doors

- Torvald’s office is divided. Has private space behind the door. Nora excluded from that space.

- Could also represent containment and entrapment within the play

- Door slamming at the end — physically represents the spaces in the Doll’s House. Nora gets her freedom by opening the door to the outside.

Scene Analysis

Letter scene

Represents a solid shift in Nora’s character

- Triggered by Torvald reading Krogstad’s letter that exposes Nora’s crime

- Nora initially ignorantly believes that Torvald will try to save her — screams that he “shan’t save her” and is fully prepared to commit suicide in “icy, black water”.

- Yet Torvald condemns her as a “miserably creature”, scornfully branding her as a “liar”, “hypocrite” and “criminal”.

- “Unutterably ugliness” — Torvald is obsessed with perfection and cannot stand anything unsightly

- Lashes out at Nora for having “no religion, no morality, no sense of duty”

- It is from this scene that Nora is pushed to forsake her doll-like nature and pursue a more authentic human experience

Final departure scene

- End of character shift of Nora and she pursues own authenticity to self

- Realises she has been but a doll to male figures in her life. She states she has been “greatly wronged”, first by her father then by Torvald. She has never had a chance to express her opinions and have them valued, from her youth as a “doll-child” till adulthood as a “doll-wife”

- Challenges Torvald’s claim that she her most “sacred duties” are to her husband and children, but rather duties to herself as a “reasonable human being”

- Realises the extent of oppression and suffering women undergo. When Torvald says “no man would sacrifice his honour for the one he loves”, Nora responds with “hundreds of thousands of women have”

- Theme of disease and recovery

- Fears that she herself has made her children to be her dolls, that their home “has been nothing but a playroom”

- Needs to “educate” herself and cannot rely on Torvald

Christine’s arrival scene:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/uk---henrik-ibsen-s-a-doll-s-house-directed-by-carrie-cracknell-at-the-young-vic-in-london-541769126-5aaaa15eeb97de00369ee92f.jpg)

| Christine’s role | Portrayal of Nora |

|

Nora is quite bluntly insensitive and is unabashed in flashing her higher social status and comfortable lifestyle.

|

| Provides exposition and reveals Nora’s character in greater depth

Christine treats Nora in accordance with her childish and immature behaviour

This incites righteous indignation in Nora, who feels insulted by what she sees as contempt. Nora confides in Christine of her secret, which she is immensely “proud and glad of”. Similar to christine, she takes pride in having provided for her family.

|

Nora’s fantasies are also revealed of a “rich old gentleman” leaving her a fortune in his will. She teases Christine by positing that the 250 pounds was gifted from a secret admirer. This

Provides additional layer to Nora’s character. Aside from her natural bubbly and childish attitude, it is apparent she does have her fair share of worries.

→ Similar to Christine, her concerns stem from providing for her family. She buys herself the “simplest and cheapest things” and scrimps and saves. → YET this contradicts with the image of Nora buying herself macaroons, a luxurious and expensive taste for a woman with financial difficulties. |

Despite how resilient and capable Ibsen has constructed Christine to be, she still suffers from the same affliction Nora does. Upon being freed from her familial obligations of a sick mother and younger brothers, she is unable to find a sense of purpose as a single figure. Christine, similar to Nora, represents a woman having been conditioned as a caretaker and a maternal figure in a patriarchal society. She does not understand how to situate herself outside of that role. |

Shows audience from the beginning that Nora does conceal a great deal from her husband. Nora also suggests revealing the secret to Torvald many years down the line when she is “no longer as nice-looking” and her “dancing and dressing-up and reciting” have lost their touch. She describes the eventuality of Torvald being “no longer as devoted” to her as the inevitable, showcasing the superficiality of their relationship and foreshadowing the eventual collapse of the Helmer marriage. Beyond Nora’s individual character, this also enriches the audience’s understanding of women in the 1800s in relation to patriarchal marriages. The self-sacrificial nature of spousal love is evident in her fear that the knowledge of her taking a loan being “painful and humiliating” for Torvald, motivating her to conduct it in secret. |